(A longer read)

When we think of the First World War, most of us think of trenches, machine guns and mud in France and Belgium.

Most of the men from Ilkeston and District who went to war from 1914 to 1918 did fight in Picardy and Flanders, but local men also fought at sea – on one of the first Royal Navy ships to be lost in that war and on one of the last. Ilkeston men also died at Jutland in the major sea battle of the war and fought the enemy at Tsingtao in China and in the Rufiji River in Tanzania. Many sailors and Marines served on the Western Front and at Gallipoli in the Royal Naval Division, which fought alongside the army in the same appalling conditions. Men from both services transferred to the Royal Flying Corps. Some volunteered for the medical services and helped their wounded comrades in all theatres of the war.

Men from Ilkeston fought Bulgarians in Macedonia and the Ottoman Empire in Palestine, Syria and what is now Iraq. They also fought alongside the Italians in Austria and in Slovenia. Some were old hands who had served in the Army or Navy for years, others were keen volunteers or raw conscripts with no battle experience at all.

These men died by accident or disease as well as by enemy action but let’s not forget that a large number made it back to a difficult homecoming, trying to re-adapt to domestic life with mixed success.

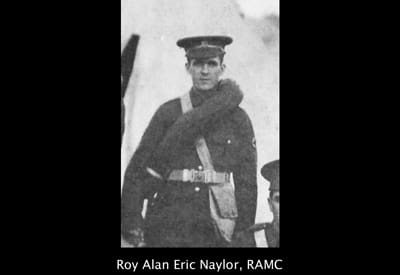

I would like to introduce you to some of the men whose stories I have researched for the book ‘Off to War’ and subsequently. First of all, Roy Alan Eric Naylor.

Aged 23 in 1914, Roy worked as a Coal Miner (loader) underground. He attended South Street Methodist Church and had seven siblings. Roy joined the Royal Army Medical Corps at the start of the war. Unfortunately, his service record was one of those destroyed in the London Blitz, but we do know that he was serving on the Western Front at Christmas 1914. Roy and at least one of his comrades were killed on 16th May 1915 near Le Touret, about five miles north-east of Bethune. He is buried next to his friend, Harry Stapleton in the Le Touret Military Cemetery. He was 23.

Two months after Roy was killed, Harry Stapleton’s mother wrote to Elizabeth Naylor from home in Tibshelf. She said “You have our deepest sympathy from a mother to a mother as nobody know what the awful blow is only them what as gone through it”.

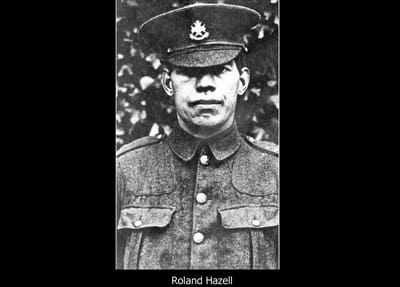

Roland Hazell was born in January 1884 near Amersham, Buckinghamshire. He married Lily Gomm on Christmas Day 1906. Roland joined the Oxfordshire Light Infantry some years before the war; his army record from this period has not survived. He came to work at Cossall colliery and moved his family here after his army service ended. Roland was called up immediately war started. Leaving Lily with three young children and another on the way, he landed in France on 24th March 1915.

The ‘Ilkeston Pioneer’ newspaper of 21st May 1915 reports that “Rowland Hazell of 12 Grass Street, Ilkeston died the death of a hero while serving his country in France. In 1914 aged 30, he re-enlisted in the 2nd Battalion Sherwood Foresters. He had only been in France for two months when he was killed by shellfire”.

The Germans were shelling a house which caught fire. Someone noticed an old lady by the building, and she was successfully rescued. She said that a small child was still in an upstairs room and Roland went to recover the child. While in the house, he was wounded in the chest and never regained consciousness. His body was originally buried in the graveyard to the convent at Le Bizet, on Belgium’s southern border.

On 8th July 1915, Lily gave birth to a daughter whom she named Lillie Le Bizet Hazell. Tragically, Lily died suddenly of a brain haemorrhage less than a year later; she was 36 and left four infant children.

Local men were everywhere that mattered in the war, and Frederick Bancroft, Enoch Baker and Frank Aldwinckle died while fighting the Ottoman Empire.

Fred Bancroft was born in West Hallam in 1875. He was married to Kate Glenn from Ockbrook. Unfortunately, we don’t have a photo of him. He had served in the Sherwood Foresters before the war, and when his ‘time expired’ he was placed on the reserve list.

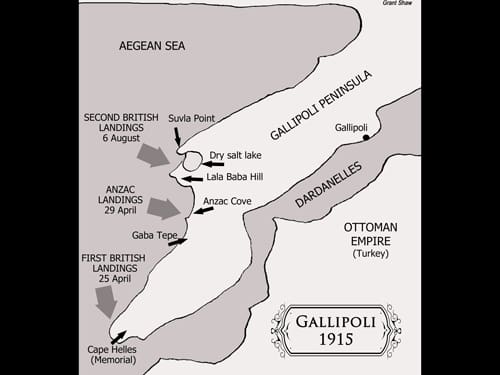

Fred was recalled to the army on 14th August 1914. Posted to the 9th Battalion The Sherwood Foresters, Fred as an old soldier was promoted to Corporal just four days later. His Division was sent to support the campaign in the Dardanelles, Turkey and they embarked ship at Liverpool on 30 June 1915, on the requisitioned liners Aquitania and Empress of Britain. On 6th to 7th August 1915, they landed at Suvla Bay on the Gallipoli peninsula, Turkey.

The plan was for a new landing at Suvla Bay to relieve the troops already pinned down at ‘Anzac Cove’. Their enemy was led by a few German officers and by a very capable and decisive general, Mustafa Kemal Pasha – now better known as ‘Ataturk’.

The landing started in chaos, in pitch darkness. Later, when the moon rose, they became targets for Ottoman snipers. Attempts to capture Hill 10 failed because no one in the field actually knew where Hill 10 was.

War correspondent Ellis Ashmead-Bartlett witnessed the landing after dawn. He could hear the fighting going on at Anzac Cove, but Suvla was fairly quiet and “no firm hand appeared to control this mass of men suddenly dumped on an unknown shore.” No real progress was made; the day was very hot and the soldiers became desperate for drinking water. The Corps suffered 1,700 casualties in the first 24 hours, which was more men than the enemy facing them had in total.

Kemal’s Turkish troops held the high ground, content to remain on the defensive. The fighting increased two days later but around noon, gunfire set scrub alight on Scimitar Hill, and the British wounded were caught in the fire. Fred Bancroft may well have been one of these, as he was killed in action that day. He was 40 years old. His body was never identified, so he is commemorated on the Helles Memorial, right at the tip of the Gallipoli Peninsula.

Enoch Baker fought with the 7th North Staffordshire (The Prince of Wales’ Own) Regiment. He was born on 22nd December 1891 in Ilkeston and in the 1911 census his occupation was ‘moneylender’s clerk’. He married Lizzie Pick in April 1915 at St John’s Church, and they had a daughter, Jessie.

By February 1916 they were in Mesopotamia – modern Iraq. On 5th October 1916 Enoch was in camp at Abu Sidra near Kut. The records show that at about 4.45pm he was shot once in the head and died shortly afterwards. A Court of Inquiry heard that Enoch had been inside his tent with his comrade Private J T Boulton, cleaning his rifle when Boulton heard a sudden shot and Enoch fell to the ground. The shot had not come from Enoch’s rifle.

An officer’s servant had been detailed to clean the officer’s pistol, which he did, leaving two bullets in the chamber. The pistol was picked up by another soldier and it discharged, firing one bullet from inside his tent into the next, where it hit the unfortunate Enoch. Private H Crewe admitted to taking the revolver out of its holster and holding it in his hand when it went off. He said he did not press the trigger. He said he had never handled a revolver and was ‘curious to see how one worked, never having seen one at close quarters before’. Evidently the court believed the accused’s explanation as to how Enoch Baker died, as the records state that Enoch was ‘accidentally killed’.

Enoch Baker was buried in the Amara War Cemetery, which was largely destroyed in the second Gulf War.

Frank Aldwinckle lived at 76 Station Road in 1901. By 1911 Frank was a miner although the census describes him as ‘injured’. This didn’t stop him being called up and he too joined the 7th North Staffordshires in June 1916.

This regiment had a reputation for profanity even by the standards of the British Army and their colourful language was well renowned. December 1916 found them still engaging the Ottoman Army in Mesopotamia. A month later Frank was killed in action. He was 31 and is commemorated on the Basra Memorial in Iraq. Frank is also commemorated on his parents’ monument in Park Cemetery, Ilkeston.

Local men were well represented at the Battle of the Somme from July 1916. Many of them fought in the ‘diversionary attack’ at Gommecourt on 1st July.

Joseph Eaton was born in 1895 in Ashover. His mother died when he was very young and his father was absent. The 1911 census finds him at Hallam Fields. He worked for Stanton Ironworks in the pipe pits as an iron pipe moulder.

Joseph joined the 1/5th Sherwood Foresters as a part time territorial soldier at Ilkeston in November 1912, aged seventeen and ten months. He landed at Le Havre on 27th February 1915, going into the front line not long after. On 1st June 1915 Joseph was taken to a Field Ambulance Station suffering from a gunshot wound to the head. He was in and out of hospital for several months, returning to the fighting each time.

On 1st July 1916, Joseph went ‘over the top’ in the attack on Gommecourt and was killed. His body was never identified, and he remained on the books as ‘missing’ until 25th August, but it was not until 13th January 1917 that the army officially acknowledged that he had been killed in action aged 21. Joe is remembered on the Thiepval Memorial, as his body was never identified.

Alban Eaton worked as a farm labourer. He enlisted in Derby and served in the 10th Sherwood Foresters, one of Kitchener’s “new army” regiments, raised from the volunteers of 1914 which shipped out to France in July the following year. Alban was killed in action on Tuesday 4th July 1916 aged 19, during a reconnaissance mission near Contalmaison in the Somme area. His body was never identified, so he too is commemorated on the Somme Memorial at Thiepval. He is also remembered on the Ilkeston Cenotaph.

Sergeant Bert Spiby of the 1/5 Sherwood Foresters was shot in the head, the bullet leaving him with a deep depression above his right cheekbone and very deaf. While injured, Bert was captured, and spent the rest of the war in prison camps. He was eventually discharged on 1st April 1919.

Sergeant Henry Shaw of Station Road, Ilkeston was killed on 1st July attacking Gommecourt Wood in the same action. Like many local boys, he started work as a pony driver down the pit (in this case West Hallam Colliery) and worked his way up to being a miner. A member of the Church Lads’ Brigade, he joined the 1/5 Sherwood Foresters in the spring of 1914. He went through the Battle of Loos in 1915 and received specialist training on the new Lewis Guns at the start of 1916. Henry had received a field promotion to Sergeant just before the battle. He was 21 when he died.

Francis Leonard Hunter Jackson was born in 1891 to parents Charles John Jackson (an Ilkeston solicitor) and Agnes Mary Jackson.

By the time he joined the Royal Naval Reserve in February 1915, Francis had qualified as a solicitor. Serving first as an ordinary seaman, he was soon awarded a commission as Sub-Lieutenant in the Howe Battalion Royal Naval Division on 31st May 1915 for service in the Mesopotamian campaign. It is not clear whether he actually served in Iraq, but if so he would have seen the siege of Kut and the battle of Ctesiphon in late 1915.

By 18th September 1916 he was sick with influenza, and he returned to England on 29th September 1916. On 6th June 1917 he rejoined his battalion and was appointed a company commander and temporary Lieutenant on 23rd October 1917.

Francis was wounded in the arm during the night of 25th October 1917 during an attack on Varlet Farm in Passchendaele. His chaplain wrote that although wounded, he “still carried on and proceeded in front of his men to investigate how things were faring. Finding that his steel helmet was interfering with the working of his compass, he discarded it altogether and so fell victim to a sniper, who shot him in the head”.

Killed in action 26th October 1917, Francis is buried in the Tyne Cot Cemetery, Belgium. He is still remembered at Varlet Farm, which is now a bed and breakfast much used by visiting Brits. His photo hangs on their wall.

Many other Ilkeston born men served in the Royal Navy and Royal Marines during the war; they fought all over the world as well as at the one major battle of the war at Jutland, where stoker Fred Wicks died when the new battlecruiser HMS Queen Mary blew up. Albert Edward Wheatley was one of the first casualties, killed when HMS Hogue was torpedoed along with two other ships in the same action off the south coast in 1914, and Herbert Saunders Nunn died in Britain’s second most catastrophic explosion when HMS Bulwark exploded accidentally in November that year.

Coming home could be a difficult and traumatic process after years of war. Almost none of those men whose families contacted us talked in any detail about their experiences. Their time at war coloured the rest of their lives and permanently changed them mentally and physically.

William Ernest Britton was one of the luckier ones in that he made it through the war after volunteering aged 17 early in 1915. Will’s service record has not been found, but his medal record tells us that he joined the Royal Field Artillery early in the war and landed in France on 29th July 1915. Surviving photographs show a marked difference between his boyish looks on going off to war and the former soldier who came back.

William’s daughter Nora Waite told me that when he eventually arrived home, his father would not allow him into the house until Will had thoroughly washed in a tin bath on the back yard as conditions in the trenches had left him infested with lice.