Introduction

The site as it appeared in early 2001. Overgrown and covered with a huge pile of garden rubbish. This view was taken looking west toward the wall which surrounds the property and divides the church yard from the grounds of the former vicarage.

Although many small scale archaeological finds have been made in and around Ilkeston over the years, no site of any major importance had ever been discovered. That is until 2001-2, when a small team of members and friends of the IDLHS and the Erewash Museum, uncovered the remains of two hitherto unknown buildings. These are believed to be the foundations of a Tudor barn, and those of an even earlier building, possibly dating from the late 14th century.

The Site: Its Location and History

The house and grounds of the former vicarage of St Mary’s, lie just a few yards east of the church and church yard of St Mary’s, which itself stands in the very centre of Ilkeston.

The house which occupies the property today was constructed in two phases. In 1842, the new vicar of Ilkeston, George Searle Ebsworth (1842-1863), arrived to take up his new post. The house in which he was expected to live had been built in 1681 and was now in a deplorable state. It took Reverend Ebsworth, three years of negotiations with his ecclesiastical superiors before a new and more fitting house was constructed.

In 1890, the house was extended on its north and east side during the residency of Edward Muirhead Evans (1887-1907). In 2000, after lying unoccupied for several years, the house was put up for sale. In the spring of 2001, the new owner of the property invited a staff member of Erewash Museum to visit the property in order to view some pieces of masonry which had been found in the garden.

The Lost Tomb of William de Cantelupe

Against the wall which separated the church yard from the property, lay a huge pile of garden rubbish and debris, heavily overgrown with weeds and creepers.

Lying against the base of this rubbish heap were several pieces of carved masonry which, when cleaned of earth and mud, bore a striking resemblance to parts of an illustration drawn in 1814, which purported to show the tomb of William de Cantelupe (died 1308).

These fragments of masonry were found buried beneath the earth and rubbish piled against the church wall. They were later found to be part of the lost tomb of William de Cantelupe (died 1309). Sections of stone window tracery were also recovered.

William had been the Lord of the Manor during the late 13th and early 14th centuries and his tomb originally stood in the chancel of St Mary’s. During the restoration of the church in the mid 1850s, William’s monument was broken up and removed from the church and subsequently left scattered around the church yard. In time these fragments became lost until found amongst the rubbish heap in the vicarage garden.

The recovery of several more sections of this masonry confirmed that parts of the long lost tomb of William de Cantelupe had been found.

The Tudor Barn

The property is surrounded by a substantial brick wall, but after clearing away the overgrowth and rubbish from the site, a 7 metre long section of this wall was found to be constructed only of sandstone. After the discovery of sandstone foundations lying at right angles to both ends of this section, it was considered possible that this was the surviving wall to a previously unknown building. At the base of these foundations, and spread across the surrounding area, were found considerable amounts of early to mid 16th century pottery sherds.

Examination of 17th and 18th century documents, and the study of the earliest known map of Ilkeston, produced by a Henry Fletcher and dated 1598, suggested that the structure to which these foundations belonged, could have been a barn, stable, or part of a whole range of buildings. Comparison of the 1598 map with modern ordnance survey maps placed a building exactly on the site of the above foundations. It was therefore considered possible that here were the remains of a building which had been in existence since at least the late 16th century.

The Medieval House

The short (and only) section of church wall constructed of sandstone.

Alongside the remains of what the team referred to as the Tudor barn, were uncovered the foundations of other walls. However, the base to one of these walls was found to lie at a lower level than those of the barn, and surrounded by large quantities of rubble, broken medieval roof tile (13th/14th c Nottingham produced), and late medieval and early Tudor pottery. At the foot of one of these (presumably) earlier walls, ran a stone lined gutter. This was found to pass under, and into, whatever the building once was. This clearly suggested that the site now contained the remains of two previously unknown buildings. The presence of so much medieval material also suggested that the earlier building appeared to date from this same period. If so when had it been built and what was its purpose?

The presence of this foundation lying at right angles to the base of the church wall suggested that the remains of a substantial structure lay buried beneath the site.

In 1386 St Mary’s came under the jurisdiction of the Premonstratensian canons of Dale Abbey. Of all the parishes which came under its control, in only four were resident priests appointed. Amongst these four parishes, the others being Heanor, Kirk Hallam and Stanton by Dale, was Ilkeston and records tell us that in the early 15th century there once stood a priest’s house and a church house in Ilkeston. It was therefore considered that these foundations may be the remains of one of these two buildings.

The Finds

During the excavations large amounts of late medieval and early Tudor pottery were found, along with over 90 fragments of medieval painted glass (13th/14th c). These finds, along with the charred material and debris, suggested that the demolition of a medieval building, and the erection of the barn had taken place in or around the mid 16th century.

Just a few of the 92 fragments of medieval painted glass found during the excavations.

The presence of, and the origin of the medieval painted glass however presented a problem. It was considered unlikely (though not impossible) that glass of this quality would have been installed in a house in which the village priest lived. The glass could have originated from Dale Abbey, where identical glass has been found. If it did originate from the Abbey, Its presence on the site could the result of it being transferred there following the dissolution of 1538. However, a third option, is that the glass may have come out of St Mary’s church following the orders of King Edward VI in 1548, to remove from churches and chapels, and to destroy, all objects bearing Papist imagery. Again, a date which would fit in with the team’s current theory

The Project Continued

Inside the two outermost foundations, another section of wall was uncovered suggesting the remains of not only one but two previously unknown buildings lay beneath the site.

Following the excavations of 2001 and 2002, further work was carried out to discover the extent of the foundations. It was discovered that the barn walls (or at least what remained of them) appeared to extend some 19 metres (64 feet) out into the lawn. A continuation of the medieval gutter was uncovered in 2003, showing that its course ran parallel to the outside of the medieval house but turned away at its south-east corner, presumably away to a midden. This would appear to fit in with the assumption that the priest house measured some 9 metres (30 feet) in length. A later resistivity survey suggested that these foundations (or at least what remains of them) may extend out into the lawn to a similar distance.

A partially reconstructed Midland Whiteware flagon found amongst the material filling the area between the above two walls pictured above.

In 2003, a second hitherto unknown water course, drain, or conduit, was discovered beneath the site, running parallel to what would have been the barn walls, but at a shallower depth than that of the medieval gutter. Again, the resistivity survey suggested that this feature may extend some distance towards the church wall. As to whether this feature is contemporary with the barn, or may date from a different period, is yet to be ascertained.

Radio Carbon Dating

In 2003, some material was sent off to Oxford University to undergo radio carbon testing. The sample consisted of a sycamore leaf, found beneath a layer of demolition material and preserved beneath a layer of clay. the leaf bore scorch marks, which appeared consistent with a surrounding layer of ash and charred material. This suggested that the leaf had fallen into the site during the time that one of the said buildings was being demolished.

This medieval bug hole cistern was also found amongst the fill material between the two walls pictured above left.

However, the results suggested that the leaf dated from between 1960 and present day. This was confusing. The leaf was lying in an area believed to have been undisturbed for at least 160 years. The leaf was found in the early summer of 2002, not in the Autumn when it could be expected to see leaves falling across the site. As mentioned above, the leaf bore scorch marks and lay beneath the demolition material which lay across most of the site.

We believe that the sample may have been contaminated by the presence of roots from a dead yew tree, now known to have been cut down in or around 1960. Despite this disappointment, a new sample was sent off in December 2004.

The site in summer 2002. Team member Carol Bamford found over 80 fragments of medieval painted glass in the area she is seen working in.

During the excavations, a number of animal bones were found. Of these, part of a cow’s jaw bone had been uncovered lying alongside the base of one of the ‘barn’ walls. It was found at a depth of around 80 cm, and lying on a bed of clay, which appears to have been lain down as a foundation to the said wall. At least a good result could indicate as to when the clay was lain down and when the barn wall was constructed.

With a 95.4% probability, the results indicate that the bone sample dates from between 1282 and 1391, but is more likely to date to the later half of that period.

With our current theory that the medieval building was demolished, and the barn erected during the mid 16th century, the results show that the sample is 150-200 years older than expected. However, the date of the sample does appear to match the period in which we believe the medieval building was erected, i.e. circa 1386.

This stone-lined gutter was uncovered during the last few days of the excavations during 2002.

Due to the extremely well preserved condition of the sample when found, it is considered possible that this bone had been buried for many years beneath the floor of the medieval building, before being dug out during its demolition, and included in the fill material found in this area of the site.

New excavations during 2005

These uncovered evidence that the material brought to the site after the construction of the new vicarage in 1847 may have originated from the area around the present Market Place. This area was cleared of farm buildings and cottages during the 1840s and vast amounts of material was removed to level the site. The area referred to had been occupied for centuries and may explain the large and varied number of finds made when the excavations in the grounds of the former vicarage cut through a layer of material which had clearly been laid to level out the vicarage gardens.

The finds mainly consisted of a jumble of medieval to early 19th c pottery sherds, evidence that the material had been removed from an area which had been occupied for some considerable time.

The stratification of the material also appeared to show that many individual cart loads had been delivered, probably over a relatively short period of time.

Another intriguing aspect was the discovery of a large concentrated deposit of glass and pottery, lying on what was the ground level outside the barn walls, before the landscaping took place.

All this material dated from between the late 18th c and the early 1840s and consisted of over 24 wine bottles, several serving dishes, a large porcelain jug, several cups and saucers, bowls and other items of tableware. This may well have been some of the household goods from the old 17th century vicarage, which the new Vicar, G.S.Ebsworth considered too old or out of fashion for him to want seen in his new and somewhat grander house.

The Foundations of a Medieval Boundary Wall

These were uncovered which corresponded exactly to where Henry Fletcher showed it to be on his map of 1598. This would have been the original boundary wall between what was once the vicarage and the demense land of the lord of the manor, land which would eventually become part of the church yard in the late eighteenth century.

Resistivity results

In March of 2005, Mr Keith Foster of the Derbyshire Archaeological Society kindly offered to carry out a resistivity survey of the site. The results of the survey revealed that the site may contain further traces of the discoveries already made, as well as possible features in areas as yet unexcavated.

Geophysics Results

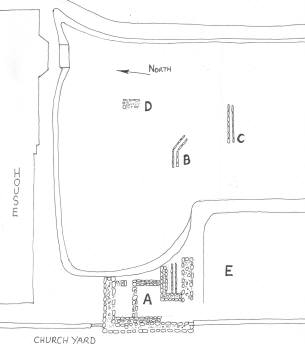

Shown at right is a basic ground plan of the excavations so far carried out.

A – The area excavated between Autumn 2001 and Summer of 2002. This work revealed the foundations to two hitherto unknown structures – the outermost of these foundations being, we believe, the remains of a barn or similar building constructed during the 16th century.

Within and just below the level of these foundations, were found the remains of what we believe to be a medieval structure, build around the late 14th century. This work also included the discovery of a gutter or water course lying at the base of the medieval walls.

B – The site of excavations carried out in the Spring of 2003, during which a continuation of the above medieval gutter was uncovered.

C – The site of a second, but presumed to be a later, gutter or water course discovered in the Summer of 2003.

D – The site of a test pit which appeared to reveal the remains of the east end of the barn.

E – The site of this year’ excavations, which are already revealing many interesting features.

The same ground plan now seen with the results of the survey overlaid.

The dark area immediately to the south of the house is very likely to be the result of building work carried out during its construction in 1845, or the extension work carried out in 1890.

However, in the areas of where the excavations have already revealed substantial foundations.

A – The continuation of the medieval gutter.

B – The site of a second gutter or water course.

C – The survey does appear to suggest that these remains (or at least what is left of them) still lie beneath the ground.

It is also possible that the gutter C continues its course towards the site of the current excavations.

The dark area adjacent to E appears to tie in with some of the features presently being uncovered.